My first trip to Japan in a year, after ten years of living there, and I’m immediately reminded why I like it. First I’m inquired of by customs, ever so politely, that it hadn’t accidentally slipped my mind to declare those firearms, drugs and pornography I might be carrying. Within a whisker, six people are loading my suitcase onto the 10:30 am ‘Friendly Limousine Bus’ and bowing in unison as we head off to downtown Tokyo. I confidently adjust my watch to 10:30. God, this country is efficient.

After a few days grappling with the urban jungles of Tokyo and Yokohama, I feel ready for a trip to the countryside. I’m also ready to see some music, and hear that the Boom are playing in Toyama, about five hours north west of Tokyo on the Sea of Japan. Two birds, one stone. The singer of the Boom, Kazufumi Miyazawa has recently released his third solo album, just issued in the UK (through Stern’s) titled Deeper Than Oceans. Although somewhat known in Brazil and Argentina, and other parts of Asia, perhaps finally Miyazawa is on his way to receiving recognition in Europe. For over ten years in Japan, he’s been a kind of Paul Simon, David Byrne and Peter Gabriel figure rolled into one, bringing various unknown music from around the world to the Japanese masses.

To get to Toyama, I have to board the shinkansen (bullet train). Even at such high speeds, the metropolis of Tokyo disappears slowly. Passing through an endless succession of tunnels cut through the mountains, we eventually emerge into open countryside. I change trains and get on the ‘Thunderbird’, in a stroke realising one of my childhood dreams.

For their latest tour, the Boom are playing at small towns and villages on open air, or specially constructed outdoor stages. “Delivering music to the people” is what Miyazawa calls it. Makes a change from the usual antiseptic Shimin Kaikan or city halls that most tours comprise. Last year the Boom had one of their biggest successes ever, with the release of their album Okinawa- Watashi no Shima, continuing their love affair with the island. In 1993, their single Shima Uta sold a million and a half copies, becoming probably Japan’s best known ‘Okinawan’ song. Somewhat bizarrely last year it became almost as well known in Argentina as well, sung (in Japanese) by actor and musician Alfredo Cassero, and chosen as the official song of the beleaguered (yes!) Argentinean football team at last year’s World Cup.

Such rare success of a Japanese song overseas became big news in Japan, and by a fate of timing, the album was released at the same time, featuring a new version of Shima Uta and other Okinawan influenced songs.

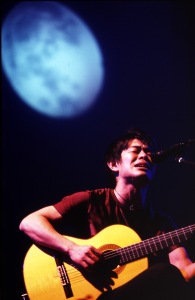

After a long bus journey from Toyama, I eventually reach the outdoor stage, in a park on the outskirts of the city, just in time for the start. To say Miyazawa has the audience in the palm of his hands is an understatement. They stand up when he stands up. They sit down when he sits down. They wave their hands when he waves his. At one point Miyazawa stands on his head. There are limitations I learn, but nevertheless Miyazawa has in abundance what I can only describe as natural charisma.

Two hours of greatest hits, and a fair smattering of Okinawan songs later, the show ends in a tumultuous finale. The whole exhausted entourage, eleven musicians and at least as many staff, retire to a Toyama restaurant. Miyazawa is clearly shattered. Today was a national holiday, he’s been touring incessantly, recording, acting in a TV drama, writing essays, books, travelling, but still graciously accepts my request for an interview. Together with two of his personal managers, we sit ourselves down at a table tucked away from the larger group, promising to be back before the main courses arrive.

I begin by asking how he first got interested in Okinawan music. “There weren’t many opportunities to listen to Okinawan music in Japan when I first started to get interested in it, so I asked friends who went to Okinawa to get some tapes for me. For me, I got the same kind of feeling or shock as when I listened to Bob Marley when I was a high school student. I really liked that the melodies were repeated often, almost incessantly, and the chorus too, the same rhythm throughout, and I thought it was very similar to reggae. That was about thirteen years ago in 1989 when we recorded our first record.”

In the 1970s, Haruomi Hosono had already found inspiration from Okinawa in some of his songs, which had not gone unnoticed by Miyazawa. “I knew Hosono was playing Okinawan music before he played with Yellow Magic Orchestra. Also, Shokichi Kina’s Haisai Ojisan was a hit in Japan in the late 70s, so I already had listened to some Okinawan music, but this was before I really got into it.”

It was the success of Shima Uta in 1993 that changed Miyazawa and the Boom forever. “I went to Okinawa to take some photos for the Boom’s third album , to a very beautiful and natural area called Yanbaru and for the first time saw a deeper side of Okinawa. I saw some remains of the war there and visited the Himeyuri Peace and Memorial Museum and learnt about the female students who became like voluntary nurses looking after injured soldiers. There were no places to escape from the US army in Okinawa, so they had to find underground caves. Although they hid from the US army, they knew they would be searching for them, and thought they would be killed, so they moved form one cave to another. Eventually they died in the caves. I heard this story from a woman who was one of these girls and who survived. I was still thinking about how terrible it was after I left the museum. Sugar canes were waving in the wind outside the museum when I left and it inspired me to write a song. I also thought I wanted to write a song to dedicate to that woman who told me the story. Although there was darkness and sadness in the underground museum, there was a beautiful world outside. This contrast was shocking and inspiring. There are two types of melody in the song Shima Uta, one from Okinawa and the other from Yamato (Japan). I wanted to tell the truth that Okinawa had been sacrificed for the rest of Japan, and Japan had to take responsibility for that. Actually, I wasn’t sure that I had the right to sing a song with such a delicate topic, as I’m Japanese, and no Okinawan musicians had done that. Although Hosono started to embrace Okinawan music into his own music early on, it was in a different way to what I was trying to do. Then I asked Shokichi Kina what he thought I should do about Shima Uta and he said that I should sing it. He told me that Okinawan people are trying to break down the wall between them and Yamato (mainland) Japanese, so he told me I should do the same and encouraged me to release Shima Uta.”

After such a spectacular and unexpected success, he next turned his attention to Brazilian music. ” I first heard bossa nova when I was high school student. I had an image of bossa nova as a kind of salon music but then found out it was completely different. I saw Joyce performing live in Tokyo and it was incredible. It was fast paced, complicated and thrilling music. I tried to do something similar with the Boom and recorded our first bossa nova song, Carnaval. I then went to Rio De Janeiro to see people’s real life, to feel and understand the local beat and went to a samba concert which was fantastic. The audience really enjoyed themselves, sharing enjoyment with others and they seemed more like the main star than the artist to me. I was in the rock music business in Japan where always the rock star is in the centre creating a dream world which was quite unrealistic. The samba scene was a new experience to me just as Okinawan music had been, and I wondered if I could make Japanese samba that the audience would want to sing together with us. I think we kind of succeeded with Kaze ni Naritai, which became a hit single. The Boom then released two Brazilian influenced albums, Kyokuto Samba (Far East Samba) and Tropicalism.”

Tropicalism was the Boom’s most ambitious project thus far, encompassing a wide range of influences that Miyazawa had encountered from Okinawa, Brazil, Indonesia and reggae, far from what a major record company might have expected of a best selling rock band. From the original four members, with the virtually full time guest musicians, the Boom had blossomed to about fifteen musicians. With his band somewhat spiraling out of control, Tropicalism was to act as a catalyst for Miyazawa’s solo career.

“Tropicalism became like my solo album eventually as I had too many of my own ideas and asked all those other musicians to play with us. Although the four of us in the Boom were still at the centre of things, we didn’t play together on some of the songs. Anyway, in retrospect, Tropicalism lacked the Boom’s own atmosphere. I had lots of ideas, so I thought I should do this experimenting solo. I could then play with musicians who I really wanted to, and do what I really wanted. The songs I write solo are generally less pop than the Boom, the lyrics are more personal.”

In 1999 he released two solo albums in quick succession, Sixteenth Moon recorded in London, and Afrosick recorded in Brazil. Sixteenth Moon turned out to be a fairly straight ahead pop album, produced by Hugh Padgham, probably best known for his work with Sting, and featuring many of the same musicians who played on Sting’s albums. “I always liked Sting very much, and I felt that as I’d been playing for over ten years, I wanted to know how far I’d come as an artist, and thought that by playing with Sting’s musicians I might find out. I wanted to find out what quality of music I could create with them. I had no idea how it would go beforehand, so I wrote the music score out and the lyrics as well, although I don’t write the lyrics down beforehand usually. I prepared an English translation of the lyrics and made a demo tape. I didn’t care at that time if it was new or not. I wanted create orthodox music of top quality, as if I had ordered a tailored suit for myself which fitted me perfectly.”

Afrosick recorded straight after in Brazil was a different affair, with some of the leading lights of the contemporary music scene that had influenced Miyazawa’s music with the Boom, such as Carlinhos Brown and Lenine. “My mind set for making Afrosick was like a fashion designer’s collection which changes every season. My mode at that time was for hip, kitsch pop, aggressive and progressive rock. I wrote the melodies and Carlinhos Brown wrote the lyrics and arranged for the other musicians with Marcos Suzano. I produced the album together with Carlinhos Brown. Suzano and Fernando Moura arranged some of the songs and then asked others such as Pedro Luiz, Paulinho Moska and Lenine to write other tunes.”

Miyazawa and his new Brazilian friends performed in Japan and Brazil. His fans lapped it up, but Afrosick didn’t manage to popularise Brazilian music in Japan, in the same way he had succeeded with the Boom. As a solo artist he was still to forge his own identity as a Japanese musician playing essentially Brazilian music. Instead it sometimes sounded like Brazilian music, just sung in Japanese.

Deeper Than Oceans probably realises Miyazawa’s own original ambition for mixing different types of music into something cohesive, original and unique to him. To help him achieve this, he enlisted the help of American Arto Lindsay as producer. They were introduced by mutual friend Ryuichi Sakamoto about fourteen years ago, after a show at New York’s Knitting Factory. “I thought I had managed to make a style that mixed different types of music, but for the new album, I wanted to make a kind of natural mixture, almost unrecognizable, so it doesn’t matter what kind of music is in that mixture. Bahian rhythms are not so unusual for me anymore, it’s a rhythm naturally inside me. It’s the same with Okinawan music. These were very different and unfamiliar years ago, but now I can use them for my own music.”

Miyazawa decided to work with some of the new generation of Brazilian musicians as well as some he had worked with on Afrosick. “I knew that Arto knows that younger generation. He heard Afrosick and told me his opinion and gave me some ideas, and we decided to work together on a new album. We’re completely different types, but I like the music he produced for artists such as Gal Costa, Caetano Veloso, Marisa Monte and Ile Aiye. I think he is an artist who gets power from playing with other artists. He gave me lots of advice during the recording and I learnt a lot. He advised me not to over express emotion too much, to sing in a natural way as the melody is strong enough to carry that emotion. If I had produced the album by myself it would have been too much in my style. I also had something he didn’t have, so this too worked well.”

Deeper Than Oceans was recorded at various locations around the world with some forty musicians roughly divided equally between Brazilian and Japanese. “First, I went to Bahia to record the rhythm tracks with six or seven musicians from Ile Aiye a famous percussion group in Bahia. I asked Juninho to play with me again, a guitarist who was on Afrosick before. Then I flew to Sao Paulo and worked on one song with a young musician, Max de Castro. After that I went to Rio de Janeiro and did some recording with Kassin, who was also on Afrosick and with Caetano Veloso’s son Moreno.”

“After finishing recording in Brazil, and just before flying to New York, our next recording location, I stopped in Buenos Aires for one day and had a meeting about recording there. In New York, we recorded at Arto’s friends’ studio. Arto is meticulous about studio work and never misses what sounds need to be recorded. He is like me as the type of artist who records the main sounds one by one in the studio but he has many more attributes that I do not have. The taste and atmosphere of Arto’s friends in New York, the rhythm tracks of Bahia and my own melodies all helped to make the music this time very interesting.”

“Back to Tokyo from New York, Arto and I continued recording for another month, including with Takashi Hirayasu from Okinawa, and after that we went down to Okinawa to record with Yoriko Ganeko . Buenos Aires was the last recording location for this project. We had already recorded Tango for Guevara and Evita in Rio de Janeiro but I wanted to make another version with real tango musicians in Argentina. The lyrics of the song were sort of flexible and I revised the words from time to time, as I wanted to make a kind of documentary song. Osvaldo Requena, one of the country’s most important tango musicians and arrangers, put a melody to my lyrics together with a tango orchestra. He read a Spanish translation of my lyrics and liked them. He said this was not only Japan’s problem, but Argentina’s as well.”

Miyazawa believes his latest solo album is probably his best suited for an international audience. ” In Brazil, I kind of recorded according to Brazilian rules, but overall the album has no nationality with traces of the chaos or disease of Tokyo. It has some elements of Japanese tradition and a very modern style as well.”

He is planning to tour in Europe later this year, having performed at a festival in Spain last year. “I like this unit of musicians very much and would like to do concerts with them in Japan as well as in Europe, but I might need to make a solo album every year with them as the circle of the Japanese music scene is very fast. It might be different in Europe, where people seem to think of what they are doing in a longer term. I want to be well prepared anyway, to always have a permanent unit to play with in Europe when I am offered any chances. I also have to think of the Boom too of course, and a ‘Best of’ was released last year in Argentina. The fact that Shima Uta was such as big hit in Argentina, while sung in Japanese, gave us some confidence that we don’t always have to sing in English.”

Suddenly realizing my promise that this would be a short interview, we return to the main table where everyone is still waiting patiently. Probably never before has the end of an fRoots interview been greeted with such a collective sigh of relief.

Next day my shinkansen arrives back in Tokyo about one minute late for which we receive a gracious apology over the train’s loudspeaker system. Two days later I arrive back at Heathrow to find the Underground isn’t running due to flooding. I decide to take a bus. While queuing up a bus driver comes up to me. “Have you got the time, mate?”. My watch may be nine hours ahead, but at least the minutes are still pretty accurate from my first morning in Japan. The bus driver adjusts his watch. I can’t but help feel there was a certain amount of irony attached to that simple question. Eventually the bus departs nearly an hour late.

Pingback: The Boom – Shima Uta | who is 2k