Like most things in Japan, the music can be bewildering to a foreigner. On the face of it, traditional culture is preserved with a devout passion; until you discover the students are only studying as a means to get married. Music schools and preservation societies abound and remain deeply conservative. While those musicians with the strength of personality to be free from institutionalisation, display an enormous capacity to create and experiment. After all, change and progression, often with a total disregard to the past, is the lifeblood of the Japanese.

The stereotypical images at the extremes bear little resemblance to reality. Unless you pay through the teeth, you’re unlikely to encounter a kimono-clad geisha plucking a shamisen (lute). Likewise, there’s little chance of stumbling upon some dead ringer copycat band playing salsa, soukous or whatever. Sadly there is one truth. The mainstream pop world is still (but less so) overpopulated by talentless ‘talentos’. This ever so-karaoke-friendly, mind numbing form of blandness is best left undiscovered. There is however a myriad of brilliant music, rooted in Japanese tradition and brought screaming into the present, that has remained buried somewhere under the quagmire of monstrosity and magic that is today’s Japan. Finally unearthed, and brought to you here on this compact disc.

Following the war, in their rush to embrace American culture, many Japanese musicians did seem to forget their own rich and diverse musical heritage. Parrot like boogie-woogie, rockabilly and jazz bands proliferated. Whatever the genre, these day’s there’s plenty of original, inspiring and challenging music, mixing up all kinds of elements. When it comes to music incorporating homegrown roots, musicians really do possess an extraordinary ability to adapt their own tradition and absorb outside influences.

While only a ‘rough’ guide to Japan’s music, just about all the major roots music styles and main instruments are presented. Not included are ‘popular’ forms such as kayokyoku, (standard popular music) or enka, akin to say American country music. The folk (min’yo) and traditional music worlds are in reality quite distinct from one another. Their inclusion together, along with modern roots music, may cause some purists to consider committing harikiri. Their idea of the ‘real Japan’ is that mystical one, before westernisation 130 years ago. This however, is the Japan of the imagination. Nothing is more ‘real’ than the happy co-existence of the old and new with a touch of kitsch thrown in.

During the post-war economic boom, Japanese people lost almost all contact with music on a daily basis. Nevertheless, a few of the songs and tunes selected for the CD, entrenched in folklore or still performed at festivals, will be familiar to almost any Japanese person. Others will be about as familiar as a pygmy chant in the rainforest.

Only in the southern islands of Okinawa is singing and dancing as much an integral part of daily life as eating or sleeping. Hence the slightly disproportionate number of Okinawan artists, and Japanese musicians who unable to get inspiration from the mainland, too turned to Okinawa.

In Japan where convenience is everything, music too often needs no effort to listen to, and no heart to perform. Okinawans put that heart back. Some of the Okinawan tracks are of the best loved folk songs, although performed in a not so conventional way. Others are less known but more radical, that push the borders of Okinawan music ever further into unchartered territory.

The Rough Guide to the Music of Japan is a comprehensive musical journey that reflects the many moods and contradictions of the nation. In the hi-tech urban jungle, the blazing neon of the advertising hoardes cast a shimmering light over the tranquility of a nearby temple. So it is with this compact disc; the past and present sit side by side, or mingle to convert into energy in an unparalleled fashion. An experience that is somehow uniquely Japanese.

1. TAKEHARU KUNIMOTO – MAKURA

Japanese often put the letter J before an adopted western entity. Hence we have the J-League, J-Pop, and here we have the original J-Rap. Kunimoto is Japan’s finest exponent of the traditional spoken art of ‘ro-kyoku’ that originated in the Kansai region. Typical stories tell of the separation of lovers, backstabbing and family feuds. Ro-kyoku was a big hit at the beginning of the century and produced Japan’s first ever recording stars. ‘Makura’ is taken from his second album ‘For Life’ which was recorded in Paris in 1993 with a mixed cast of Japanese and African musicians. Kunimoto’s word play is accompanied not by a Japanese drum but the djembe of Maré Sanogo, which sounds uncannily Japanese anyway.

From the CD “For Life” – For Life Records

2. KAWACHIYA KIKUSUIMARU – KAKIN ONDO

Kawachi Ondo was originally music to accompany the bon-odori (festival of the dead) in Kawachi, a suburb of Osaka. As far as I can make out, there are only two refrains, played on guitar and accompanied by a drum, which are repeated over and over, with a kind of mesmeric effect. Attending a Kawachi Ondo festival is like stepping back in time, as hundreds of dancers move in a circle around a center stage, dressed in yukata (summer kimono). Kawachiya Kikusuimaru is Kawachi Ondo’s most famous traditional singer, although also it’s prime innovator. He was once releasing CDs nearly every month of his shinbun yomi (newspaper readings), setting his opinions on current events to Kawachi ondo. A flamboyant character, he’s constantly dressed in kimono, and has friends in high places. Kakin Ondo is not Kawachi Ondo at all, although the vocal style unmistakably is. Driven by a reggaefied beat, the story tells the fortunes of an ‘arbeiter’ a part-timer, and was used in a TV commercial, which brought Kikusuimaru national fame.

From the CD “Happy” – Pony Canyon

3. SOUL FLOWER MONONOKE SUMMIT – FUKKO BUSHI

At the beginning of 1995, the city of Kobe was devastated by the Great Hanshin earthquake. Takashi Nakagawa from nearby Osaka decided to take his group Soul Flower Union to the streets of Kobe, to ‘cheer up’ the victims. In the abscence of electricity, his band were forced to go ‘unplugged’. They swapped electric instruments for Okinawan sanshin, and chindon, a percussive instrument used with clarinets and brass instruments. (see track 19). They played mainly old Japanese songs, including ‘Fukko Bushi’. Based on a traditional Chinese melody, ‘Fukko Bushi’ was the most popular song in the ruins of the Kanto earthquake that struck the Tokyo area in 1923. Nakagawa put new words to the melody, which included lines about ‘Nagata’ in Tokyo, the government area being rich, and Nagata in Kobe, an area of mainly immigrants, being poor. Too controversial to release for their major record company, the group formed the ‘punk chindon’ unit Soul Flower Mononoke Summit, and released a record themselves. The result is some of Japan’s most infectious music of recent years.

From the CD “Asyl-Ching Dong” – Respect Records

4. MICHIHIRO SATO – NIKATA BUSHI

Every now and then, something catches the collective imagination of the nation, and experiences a ‘boom’. Responsible for the Tsugaru shamisen boom in the mid-1970s was recently deceased blind player Takahashi Chikuzan. Tsugaru is an older name for Aomori, in the north of Honshu the main island of Japan, and the shamisen is a lute like instrument. Known for it’s harsh cold winters, the folk music of Tsugaru is perhaps mainland Japan’s most exciting. The shamisen is plucked with amazing speed in intricate patterns and semi improvisations. Michihiro Sato, one of the best of the younger players, is an apprentice of another great player Chisato Yamada. On this version of Nikata Bushi, Sato’s shamisen is accompanied by shakuhachi.

From the CD “Jonkara” – Kyoto Records

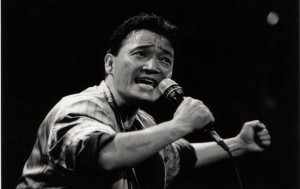

5. TAKIO ITO & TAKIO BAND – TAKIO’S SORAN BUSHI

One of Japan’s greatest vocalists, Takio Ito, the son of a fisherman, was born in Hokkaido, the Northern island of Japan. He grew up listening to the singing of his father as he worked, including this song, a Hokkaido min’yo standard that relates the life of a herring fisherman. He was a brilliant min’yo singer from an early age. A certified teacher at 18, he won the national min’yo championships three years running. However, he found the confines of belonging to the somewhat staid Min’yo assocaition, stifling for his creativity and promptly quit. Ever since, Takio has been expanding the realms of min’yo further and further, incorporating jazz, rock and other Asian traditional elements. At the end of the 19th century the government tried to root out traditional min’yo, as it was not deemed suitable for a western-style nation, and is perhaps Japan’s true ‘popular’ music. Takio’s driving, powerful versions of ‘Soran Bushi’ have become the highlight of his recorded output and live shows. Pumping your fist in the air to the response calls is obligatory.

From the CD “Ondo” – VAP Inc.

6. YASUBA JUN & AN-CHANG PROJECT – AMAGOI BUSHI

Yasuba Jun is the third ‘part time’ member of a Japanese female duo, Shisars who update Okinawan traditional folk with bits of honking sax and grunge-like guitar among other things. Yasuba Jun didn’t find time to appear on Shisars’ excellent album, but fortunately did find the time to make her own, equally brilliant solo album. Featuring one half of Shisars, and the same fine guitarist, her album is even more raw and sparse, with a sense of naiviety that makes it utterly refreshing. She doesn’t play the usual Okinawan sanshin, but it’s older cousin from China, the slightly bigger sangen. Yasuba Jun drew her inspiration from the usual ojisan and obachan (old folk) she observed singing and dancing in Okinawa. Amagoi Bushi is a traditional folk tune of Yonaguni island, the western most island of Japan, where she once worked in a sugar factory. No hint of saccharine here, just Okinawan music made naturally sweet.

From the CD “Yarayo-Uta no Sahanji” – Mangetsu Records

7. TAKASHI HIRAYASU – MANGETSU NO YUBE

Takashi Hirayasu was once guitarist with possibly Okinawa’s most famous group, Shokichi Kina and Champloose. He was an important contributor to some of the band’s classic material, including the1980 album ‘Bloodline’ featuring Ry Cooder. After quitting Champloose he set about putting together an album to encompass his wide ranging musical influences.Among the unmistakably Okinawan melodies are rock guitars, plus African and Caribbean rhythms. Mangetsu no Yube (A Full Moon Evening) was written by Takashi Nakagawa of Soul Flower Union (see track 3) and Hiroshi Yamaguchi of the group Heat Wave, for the victims of the Kobe earthquake. The song is fast becoming a classic of Japanese music, in much the same way as Kina’s ‘Hana’ before. Probably, the best Japanese song of the 1990s.

From the CD “Kariyushi no Tsuki” – Respect Records

8. AYAME BAND – HIYAMI KACHI BUSHI

It’s time to put your arms in the air. Now bend your elbows slightly, relax your wrists, and then wave your arms and hands in the air, like a snake being charmed. For added effect run on the spot, or alternatively just jump. You’re now doing the Katcharsee. The dance the Okinawans love to do to the faster songs, and also the name of the upbeat style of music. Hiyami Kachi Bushi is classic Katcharsee, here performed by Ayame Band, led by another ex-Champloose member, sanshin player Takao Nagama. The sanshin is the 3 stringed snake-skinned banjo at the heart of all Okinawan music, and Nagama, from the Yaeyama islands, is known for being one of its fastest players. Much like Kina, he formed his own family band featuring his brother as keyboardist/arranger, with his sister leading the chorus. As yet, Ayame Band CDs and concerts have been exclusively confined to Okinawa. If the katcharsee is too energetic, this version allows you to follow the sanshin part with a simple guitar hero pose.

From the CD ” ‘Akemio No Machi Kara’ – Kokusai Boueki

9. TADAYOSHI IKAWA – MOJI BANANA NO TATAKIURI

“Roll up, roll up, get you’re banana’s here!”. Japanese had never seen a banana until the start of the Meiji period, towards the end of the 19th century. They first entered Japan through the port of Shimonoseki, facing Korea in the west of Honshu on the Sea of Japan. The nearest major city was Kitakyushu, right at the northern tip of Kyushu, the southern of the main Japanese islands. It was here that ‘Banana no Tatakiuri’ selling bananas with this colourful, rapping and stick beating began, in the town of Moji. Strangely enough it even exists, in pockets, until this day.

From the CD “An Account of BANAtyans” – Active Voice

10. OKI – UTUWASKARAP

Oki (Kano) is a musician of mixed Japanese and Ainu (native Japanese) blood. Upon discovering his background , he followed his Kamuy instinct, the Ainu spirit, and moved to Hokkaido, the ancestral home of the Ainu. His cousin gave him a tonkori, a skinny, five-stringed wooden instrument, and suggested Oki bring the Tonkori and Ainu culture out of the past and into the present. The Ainu are said to be close to nature, but have never had their own land or the chance to develop their culture or socialogical status. Oki intends to rediscover the identity of the Ainu, with the creation of a new Ainu music. Utuwaskarap means ‘Let’s Understand One Another’ and takes nature and harmony as it’s theme. “People created by kamuy and brought up on this earth, shouldn’t hate one another. I’ll be waiting with hope.”

From the CD “Kamuy Kor Nupurpe” – Chikar Studio

11. SHOZAN TANABE – NYORAI SHIZUNE

Whenever a Japanese, or even Asian, character or scene is introduced in a film, invariably it will be accompanied by the drifting sound of the Japanese bamboo flute, the shakuhachi; supposedly evoking all the mysticism of the Orient. The origins of the shakuhachi can be traced back to early 7th century China. It has strong associations with Zen Buddhism, and was played by the itinerant monks, Komuso, during the Edo period. There are two streams of music, myoan the purely meditational, and the other that concentrates on the more musical aspects, of which there are two major schools, Kinko and Tozan. Both of these include gaikyoku, ensemble pieces, and honkyoku, ‘original, true, music’ for solo shakuhachi. It is within Honkyoku that the uniquess, and tonal possiblities of the shakuhachi can be appreciated. A sense of serenity, the lack of any rhythm or melody, half tones, quarter tones, the silence. Shozan Tanabe is one of Japan’s finest young players of the Tozan school, that introduces elements of western music. Nyorai Shizune is a modern composition that translates as ‘Tranquility of the Great One Truth’ that demonstrates the versatility of the instrument and the expression of the performer.

From the CD “Shizuka Naru Toki” – Kyoto Records

12. YUKIHIRO GOTO – UBUE

The Japanese biwa has it’s origins in ancient Persia, and is related to the Arabic oud. It’s believed the biwa entered Japan in the 6th century, specifically to Satsuma, the modern day city of Kagoshima and the southern most city of mainland Japan. The Satsuma biwa tradition, is the longest established in Japan, and in it’s playing technique is sometimes compared to the Delta Mississippi Blues. Yukihiro Goto, is a young player of the Satsuma biwa, who was equally influenced by American blues music. Ubue is a recent composition written by accordion player Aki Tamura, and also features shakuhachi.

From the CD “Poetry of Japanese Ballads on Biwa” – Zanmai Records

13. TETSUHIRO DAIKU – ASADOYA YUNTA

There is a no more respected musician in Okinawa than Tetsuhiro Daiku. A civil servant by day, he stills find time to teach hundreds of students, record albums, and perform live regularly in Japan and around the world. Daiku san (as he’s always called) is from the Yaeyama islands, about 300 miles south west of the main Okinawan island. Yaeyama shima uta (island songs) are quite different to those of Okinawa. The music, originally just vocal, grew out of the fields as working songs, known as Yunta & Jiraba, (also the title of the CD, from which this track was taken). He recorded several albums of traditional shima uta, before a meeting with Japanese saxophinist Kazutoki Umezu led him in a new musical direction. Mixing mainly Yunta & Jiraba with jazz and chindon, with an array of brass and stringed instruments, each album in this style has been groundbreaking.Asadoya Yunta originated on the island of Taketomi, the most unspoilt of all Okinawan islands, where time seems perpetually frozen and the means of transport is still water buffallo drawn cart. It’s the most popular song from Yaeyama, and is among the best known of all Okinawan tunes.

From the CD “Yunta & Jiraba” – Disc Akabana

14. THE SURF CHAMPLERS – JAMES BOND THEME

The name is Yano, Kenji Yano. He was born in Osaka, but now makes Okinawa his home. He was a member of a group Rokunin Gumi in the 80s, who in concert reportedly could match Kina and Champloose in their heyday for pure passion, but who sadly never recorded an album. Always ahead of his time, and experimenting with new sounds, under the pseudonym of The Surf Champlers, in a master stroke he mixed mainly Okinawan Katcharsee classics with surf music. Producing, mixing, recording and playing all instruments himself. By the sound of it, in his bedroom. Virtually unknown in Okinawa or Japan, just recently he’s been getting some attention with his new project, “Sarabandge”, Okinawan Trance Music.

From the CD “Champloo A Go Go” – Qwotchee Records

15. MAKOTO KUBOTA & THE SUNSET GANG – HAISAI OJISAN

Two seminal figures for bringing Okinawan, Asian and other ‘world’ musics to a Japanese audience are Makoto Kubota and Haruomi Hosono. Kubota and his band, featuring Hosono on drums and as co-producer, recorded Shokichi Kina’s classic ‘Haisai Ojisan’ in 1975. Arguably they created the first wave of interest in Okinawan music in Japan, Kina having a hit with his song two years later. Due to a now slightly dodgy original master tape, this version was slightly remixed by Kubota in 1989, and features Sandii on backing vocals. Kubota and Hosono have never swayed from their pioneering spirit. Kubota producing several Indonesian artists including Detty Kurnia and an ecclectic assortment of music with Sandii. Hosono, perhaps Japan’s only musical genius, seems to be the spark that lights everything, from folk and ‘group sounds’, to technopop and ambient.

From the CD “13 Classics” – Vivid Sound Corporation

16. YASUKO YOSHIDA – AGARI JO

With the departure of Misaka Koja, Yasuko Yoshida is now the chorus leader of the female quartet Nenes. Together with Kina and Rinken Band, Nenes have been at the forefront of the Okinawan music scene for nearly a decade.Their fans around the world include Ry Cooder, with whom they recorded in 1994, and Talvin Singh, for whom they supply backing vocals to the title track on Singh’s album ‘OK’. Nenes performed at the 1998 WOMAD festival in the UK, and took part in the subsequent Real World recording week. Taking a more simple and traditional approach than the ‘Uchina pop’ of Nenes, this recent composition features Nenes mentor Sadao China on sanshin and also ryukin, the Okinawan koto or harp. Although not at the same time, I imagine.

From the CD “Iijiyaibi” – Marufuku Records

17. KOTO VORTEX – HO NA MI

Koto Vortex are four women who met while studying the koto under Kazue and the late Tadao Sawai. The Sawai’s were known for their innovative approach to the koto, and while following in their teacher’s quest for breaking the mould, Koto Vortex take the koto along their own path of exploration. The harp-like koto is probably the most conservative of the Japanese traditional instruments, originating in China and being absorbed into Japanese court music. Studied by young girls and taught by old women as a virtuous exercise before marriage, there is a massive void between the ages, of serious performers. Koto Vortex fill that void, and bring the koto vibrantly to life. The compositions they perform are often minimalistic and repititious, but hypnotic and intoxicating.

From the CD “Koto Vortex 1, Works by Hiroshi Yoshimura” – Paradise Records

18. EITETSU HAYASHI – UTAGE (excerpt)

Kicked out of bed at 2 am to go for a run in the freezing cold. Forbidden to offer more than just a cursory glance at a member of the opposite sex. A full length marathon a day. Remuneration, zero. The small print in the job description of being a member of Sado Islands first drumming group Ondekoza, a group ‘in search of the generative power and origin of the Japanese people’. Some would discover their rebellious spirit, and form a breakaway group Kodo. Eitetsu Hayashi the lead drummer with Ondekoza, had been with the group for 11 years. He joined Kodo at it’s inception but soon decided to break out on his own. The only member with a background in rhythm, Hayashi is undoubtedly the star of ‘wadaiko’ (Japanese drum). With it’s roots in Kagura, music offered to the gods, it evokes the sounds of nature- the roar of thunder, the crash of the surf, and the melodic hum of the breeze. Hayashi adds to that tradition with a dazzling array of instruments and sounds. On this piece he is accompanied by the nohkan, a horizontal flute.

From the CD “Eitetsu”- King Record Co. Ltd

19. CICALA MVTA – SHI CHOME

Before the TV commercial, there was the chindon commercial. Musicians dressed in colourful costumes would walk the streets, carrying a banner, blowing saxophones and clarinets, usually led by a woman carrying and banging the three drums of her chindon. Clarinet and accordion player Wataru Ohkuma first helped to bring this colourful instrumental music storming into the present with the group Compostella. He also added the chindon sounds to albums by Tetsuhiro Daiku and Soul Flower Mononoke Summit. Cicala Mvta is the name of his own unit whose repertroire mixes influences from chindon to Klezmer, Balkan, Turkish and Nepalese music. Shi Chome builds ceaselessly in a never ending climax before screeching to halt with the chindon cello saw massacre.

From the CD “Cicala Mvta” – Respect Records